Authorities believe the drones were intended for use in conflict zones, possibly against Israeli or Jewish targets. The case has sparked alarm among Jewish leaders and security experts, who say it reveals how terrorist organizations are embedding themselves in the heart of European cities.

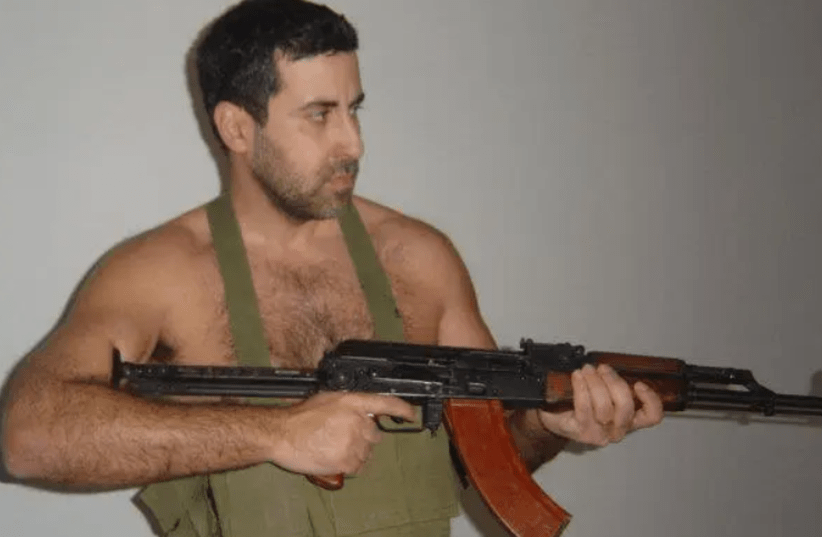

Hezbollah-linked arrests in Spain are not new. In July 2024, a joint Spanish-German security operation led to the arrest of four individuals suspected of belonging to a network that supplied Hezbollah with components for manufacturing exploding drones. Three of the suspects were detained during raids in Barcelona and Badalona, while a fourth was arrested in Germany. Among those arrested were two Spanish citizens of Lebanese origin who worked as businessmen. Authorities believe the network, considered one of Hezbollah’s primary suppliers of drone parts in Europe, was responsible for producing 1,000 drones intended for attacks on northern Israel.

For many, the revelation is jarring not only because of the threat it represents, but because of where it happened. Barcelona is known for its architectural beauty, Mediterranean pace and cosmopolitan rhythm. Tourists fill its plazas with dozens of languages, musicians play in the subway and the scent of seafood and fresh bread drifts through narrow streets. The city has long projected an image of safety and harmony. That image is now under strain.

He warned that the Spanish government’s posture has shifted from passive tolerance to something more dangerous. He pointed to political factions such as Sumar and Podemos, part of the current governing coalition, and their well-documented associations with groups like Zanidún and Mazarbadil—two organizations he described as “ideologically and operationally close to Palestinian terrorism.” (Zanidún is known for staging aggressive anti-Israel protests, while Mazarbadil has hosted events featuring members of groups designated as terrorists by the EU.)

Asked what the Jewish community can do, Mas offered a grim outlook. “The police are professional. The intelligence services are competent. But none of that matters when the political leadership aligns with the aggressors. What can the Jewish community do? Either push for regime change—or pack up and leave.”

“In the UK alone, over 3,500 antisemitic incidents were recorded—more than 200 of them violent assaults,” he said. “In France, the number of physical attacks was the highest ever reported. And in Denmark, we saw a 70% increase—including arson and knife attacks against Jews on the street.”

Srulevitch cited polling that shows deep-rooted biases remain widespread. “Seventeen percent of Western European adults still hold multiple antisemitic beliefs. That’s one in six,” he said. “It touches every Jewish person—not just in acts, but in attitudes. It’s the air we breathe.”

He warned that antisemitism is increasingly disguised as political protest. “Organized anti-Zionist groups are holding demonstrations in front of synagogues instead of embassies,” he said. “That’s not protest—it’s intimidation. It’s antisemitism by textbook definition.” He added that universities and public institutions are “bystanders at best, enablers at worst.”

Ron Brummer, deputy director general for combating antisemitism at Israel’s Ministry of Diaspora Affairs, said the post–October 7 climate has transformed both the volume and nature of antisemitic threats. “This is no longer just about numbers,” he said. “Since October 7, antisemitism has become more violent, more dangerous, and most worryingly, more tolerated.”

Brummer said the change is affecting how Jews live across the continent. “In countries like France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, people have to think twice before wearing a kippah, sending their kids to a Jewish school, or walking near a synagogue,” he said. “It’s a deterioration in quality of life. Not only because of increased attacks, but because society at large has become disturbingly tolerant toward antisemitism.”

Israel’s Ministry of Diaspora Affairs operates a 24/7 war room that monitors antisemitic threats across digital platforms. Brummer said what they’re seeing now is institutional, not just fringe. “Antisemitism is no longer confined to fringe voices or isolated incidents,” he warned. “We’re seeing it embedded in universities, cultural spaces, media, and even local and national governments.”

He said that the rhetoric has grown more sophisticated since the October 7 attack. “NGOs don’t openly endorse Hamas or Hezbollah,” he said, “but their narratives do. They’ll condemn October 7 with one breath, then justify it with the next—accusing Israel of genocide, war crimes, or inventing grotesque lies like mass rape or deliberate infanticide in hospitals. This is no longer criticism of Israeli policy—it’s psychological warfare against the legitimacy of Jewish existence.”

Pilar Rahola, a former member of Spain’s Congress of Deputies and former deputy mayor of Barcelona, called the arrests “a wake-up call that nobody heard.” In an interview with The Media Line, she said: “The detentions happened in Eixample, right in the center of Barcelona—just blocks from the main synagogue and Jewish school. And yet, the press barely mentioned it. It’s like it’s not even our problem.”

She said the atmosphere for Jews in the city is one of quiet regression. “My Jewish friends hide their kippahs and Stars of David. The only school in the entire city with police at the entrance is the Jewish one,” she said. “We are turning abnormal into normal. This is a return to the ghetto.”

Rahola said the problem extends far beyond Barcelona. “It’s happening across Europe. There is an ambient antisemitism, fueled by anti-Israel hatred, but also by something older—an idea that the Jew is always suspect,” she said. “The community doesn’t become more alert when something like this happens—they are already alert, already living as targets.”

She criticized the Spanish judiciary’s response to the case. “Only one of the three suspects was placed in pretrial detention. The others were released with minimal restrictions,” she said. “It’s incomprehensible. These are people connected to one of the most dangerous terror organizations in the world, caught building drones in the middle of a European city—and the system lets them go.”

Rahola said that because Hezbollah is often viewed as a foreign threat, institutions don’t take its presence in Spain seriously. “If instead of Hezbollah they had been former ETA members, the judicial response would have been entirely different,” she said. “But Hezbollah is seen as something far away—Lebanon, Syria, Israel’s problem. No one understands that this is not foreign. They were here, and they were building drones for war.”

Brummer agreed. “The real threat lies not just in drone factories or online hate, but in society’s shifting moral compass,” he said. “When the world tolerates antisemitism in the name of liberalism, it stops being liberal.”

Srulevitch added: “Security is everything. Without it, nothing else matters. Thankfully, in Barcelona, the state acted in time. But how many more cells are out there?”

The case has left behind an uneasy question for Spain and for Europe more broadly: Will governments act before the convergence of terrorism and antisemitism grows into something far worse? The discovery of Hezbollah operatives allegedly building weaponized drones in the heart of Barcelona has made that question impossible to ignore.