Over nearly two weeks, southern Israel endured repeated barrages. On June 20 alone, more than 70 sites across the Negev — many in Be’er Sheva — were struck by shrapnel and interceptor debris. Older residential neighborhoods lacking reinforced rooms suffered serious damage.

Soroka, the region’s main hospital serving some 700,000 people, sustained catastrophic damage. The old surgical wing, which took a direct hit, resembled “a scene from an end-of-the-world movie,” said Dr. Yarden Nevo, the hospital’s deputy director.

“This is a serious structural issue. A hospital of this scale, completely unfortified,” he explained.

Damage estimates range from 500 million shekels to over a billion shekels. Roughly 500 beds were lost, along with entire departments, including urology, ENT and ophthalmology. “I arrived to see fires still burning. It was an apocalyptic scene. We’re now racing to restore the hospital’s functionality,” said Nevo.

One senior staff member said the missile damaged several employees’ homes and deeply shook the workforce. “One veteran doctor whose department was hit just broke down crying. This has human and emotional consequences you don’t recover from easily.” Yet, Soroka treated 26 wounded patients — two in moderate condition — and continued operating under extreme pressure. “If a medevac from Gaza arrives, we’re ready. We’ll treat whoever needs it.”

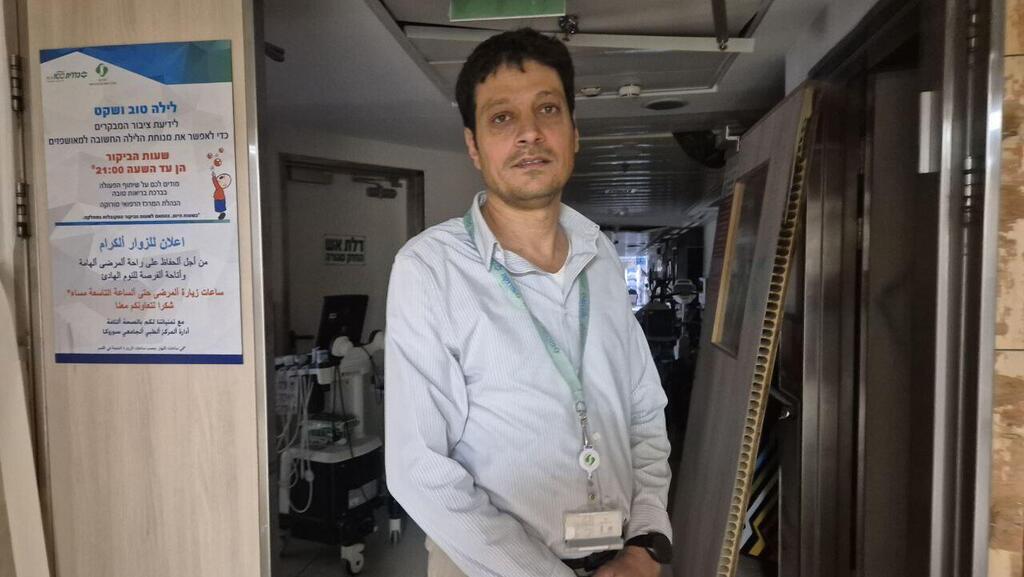

Dr. Tzachi Slutsky, Soroka’s deputy director, was abroad when the missile hit. “I told my wife, ‘I’m going home no matter what.’ I flew from Montenegro to Athens, then found a way back with Arkia. It took 15 hours. I went straight from the airport to the hospital — and saw that my second home had been destroyed.”

Slutsky oversees surgical operations and operating rooms, many of which were heavily damaged. “I’ve been with these departments for years — it’s painful, surreal. But we’re here 24/7. The hospital is functioning and expanding every day.”

Eight hospital staff members lost their homes. Nearby Ben-Gurion University was also hit hard: 50 faculty members were left homeless, 48 students were affected, six research labs were destroyed, and another nine were severely damaged. The damage to the campus is estimated in the tens — if not hundreds — of millions of shekels.

Tamar Setter, a postdoctoral student and daughter of one of the victims, described the reality in the university’s student village in the Ramat neighborhood: “My husband works at the university. From day one, they supported us. But this is a new reality. There’s so much bureaucracy, and we still don’t have a permanent housing solution. I was so worried about my family in central Israel, but the worst hit was right here.”

Simone, who lived in one of the damaged buildings, recounted: “The window flew into the bathtub. The door frame blew into the stairwell. The city gave a good initial response, but we have no idea how long we’ll be displaced. The uncertainty is unbearable.” Three buildings have been deemed uninhabitable after direct hits, and dozens more — though intact from the outside — have sustained structural damage, leaving residents unsure of their future.

Roughly 700 residents have been registered at Be’er Sheva’s evacuation center and relocated to hotels in the city, the Dead Sea, and the Ashlim Center. Even the Leonardo Hotel and student dorms have been converted into temporary shelters. “These strikes are on a completely different scale than what we’ve seen before,” said Mayor Rubik Danilovich. “We’re dealing with a much wider front. Housing isn’t the issue — it’s the uncertainty, the sense of the future.”

Amid the devastation, there have been sparks of hope. Over 100 babies were born at Soroka during the attacks. “In darkness, we light a flame,” said Dr. Eyal Sheiner, head of the maternity ward. “Each birth is a victory. A message: We’re here. We’re not going anywhere.”

Hundreds of Be’er Sheva residents remain scattered across temporary shelters. At the Ashlim Center in Neve Noy, evacuees from the Ze’ev neighborhood were met by social workers and psychologists.

“I feel completely lost,” said Anya Obsyanko, whose home was hit. “You can’t live like this. When the missile landed, I told myself: We need to leave this country. I get it now — this will never end. The next war will be worse. My daughter’s on the autism spectrum, and she cries constantly. My two sons are stressed. This is just how it will always be.”

Others, like Yevgenia Khaimovich, insist they’re staying. She was waiting for a room at the Ashlim Center. “We have a shelter in the building. I went down once, then the sirens started. The stairwell door blew open from the blast. The windows shattered, the door’s destroyed. I don’t know when we’ll be able to return — we have so many questions. I just want peace. People here are scared, but this is our city. I’m not leaving Be’er Sheva.”

Nitza Dadia shared her trauma: “We’re calmer now, but the fear and hysteria were overwhelming. I thought I was going to die in that shelter. I said the Shema prayer. The building shook. When I opened the door, everything was destroyed.”

At the Leonardo Hotel, time is running out for evacuees. Several nearby buildings were badly damaged, but the city has begun urging families to return. “They asked us to go back,” said Sharon and Nadine, who live in one of the affected buildings. Nadine recalled, “I contacted the municipality. A social worker told me, ‘Be strong, you’ll get through this. It’s on you now.’ What kind of response is that? They told me, ‘Not everything is our responsibility.’ Maybe the budget is running out. The social worker asked, ‘What will you do?’ I said, ‘I guess we’ll rent.’ But who’s going to pay? No one’s telling me anything. The initial help was great — but now I’m more confused than ever.”

Nadine, a speech therapist who works from home, and her partner feel they’ve fallen between the cracks. “Even if we rent, we’ll lose money. We’re not eligible for property tax relief, and we’re not sure we’ll qualify for rent assistance.”