Trailer for The Sacred Society

It described how volunteers performed sacred rituals to prepare the deceased for burial with dignity, a process rooted in centuries-old Jewish tradition. Moved by their dedication, Zelkowicz decided to confront his fear of death by volunteering with the Chevra Kadisha in Columbus, Ohio, where he now resides with his wife and two children.

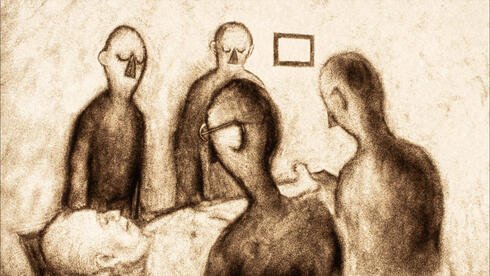

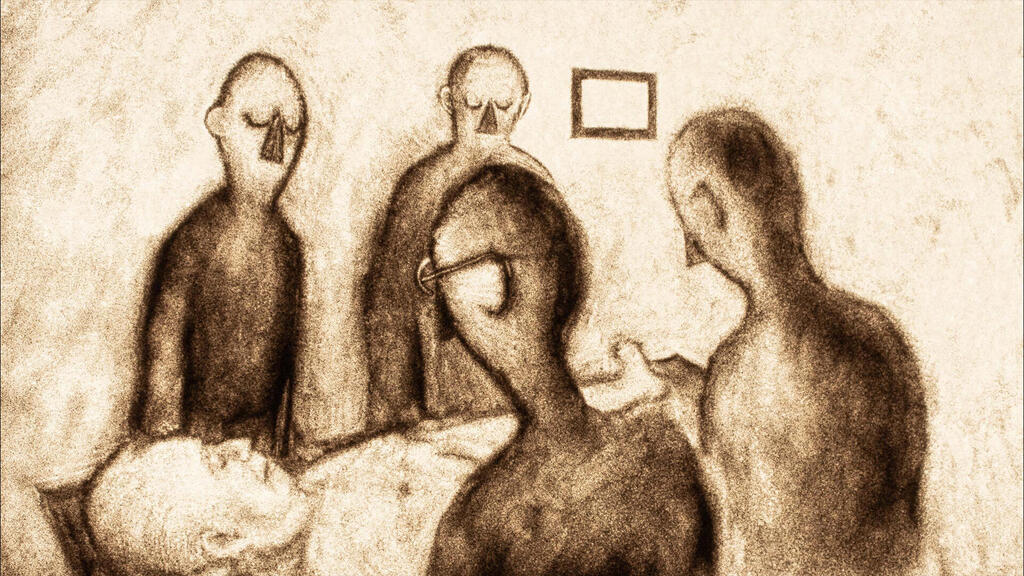

This experience inspired Zelkowicz to create The Sacred Society, a 12.5-minute animated short that captures the emotional weight of the Chevra Kadisha’s work. Using sand animation, a technique where images are drawn and erased in sand to create fluid visuals, the film features the voices of American Chevra Kadisha volunteers, including Zelkowicz himself, as they describe preparing bodies for burial.

“I’d read about the Chevra Kadisha after tragedies like Pittsburgh or events in Israel, but I wasn’t aware of their daily work,” he told Ynet. The organization, rooted in Jewish law, performs “tahara”, the ritual purification of the deceased.

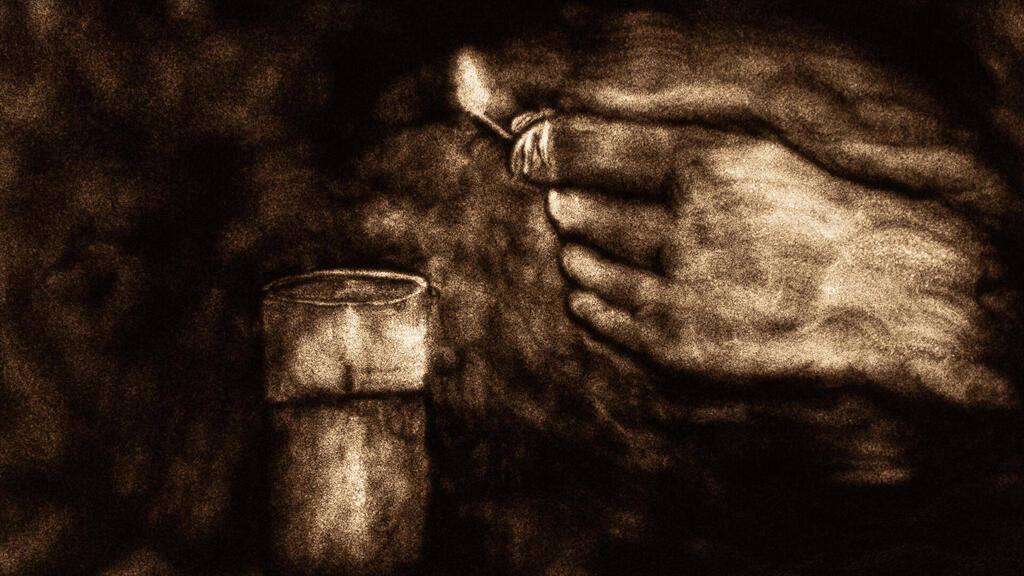

Volunteers wash the body multiple times, clean it thoroughly and dress it in simple linen shrouds, known as tachrichim. Men handle male bodies, women handle female ones, ensuring modesty and respect. In cases of violent death, such as the Pittsburgh victims, bodies are buried in their clothes to preserve all blood, adhering to Jewish principles that honor the deceased’s physical remains.

As a self-described Jewish atheist, Zelkowicz finds meaning in these rituals despite not believing in a divine framework. “I went to Jewish school, and Judaism has always been a big part of my family and identity,” he explained. “We host Shabbat dinners, and my kids attend Jewish school. When I get a call about a community member’s passing and perform these rituals to honor them, it’s valuable to me without needing a supernatural explanation.”

For Zelkowicz, the act connects him to his heritage, to his grandparents and to Jewish communities across centuries. “It’s about making death less frightening by engaging with it directly,” he said. “It ties me to my community and to Jews from a thousand years ago.”

The film highlights a poignant aspect of the tahara process: dressing the deceased in white shrouds that symbolize the garments of the High Priest in the ancient Temple. “Everyone, no matter who they are, is dressed like the High Priest entering the Holy of Holies on Yom Kippur,” Zelkowicz noted. “It’s a beautiful equalizer.”

This ritual underscores Chevra Kadisha’s mission to treat every individual with equal dignity, regardless of status or circumstance. Zelkowicz conducted seven hours of interviews with fellow volunteers, uncovering diverse perspectives. “I asked if they believe in God. Some do, some don’t,” he said. “What’s fascinating is that we’re all drawn to this practical act, regardless of our theology.”

Volunteering is unpredictable, with calls coming sporadically. “Sometimes we go four or five weeks without one, then get three in a week,” he said. A group chat alerts volunteers: “So-and-so passed. Who’s available tomorrow at seven?” Zelkowicz joins when he can, grateful for a robust team.

He’s met deeply religious volunteers and others unaware of Chevra Kadisha’s role until tragedy struck. “I’m shocked at how little people know about this,” he said. “It’s not taught, and there’s a secrecy to it.” Yet, he’s heard from community members who lost loved ones—an aunt, a sibling, a parent—who found solace knowing volunteers treated their relatives with care and respect.

The film doesn’t shy away from difficult topics, like preparing children for burial. Though Zelkowicz hasn’t personally handled such cases, other volunteers shared their experiences. One veteran admitted that preparing a baby might be too overwhelming to continue, while another insisted they’d always respond when needed.

Zelkowicz, a stop-motion animator, professor at Ohio State University and former animator for Robot Chicken, The Simpsons and The Lego Movie, chose sand animation for its symbolic resonance.

6 View gallery

IDF’s Shura base after the October 7 massacre, where victims’ bodies were brought for preparation according to Jewish burial rites

(Photo: Yair Sagi)

“In school, everyone hated it, but it felt right for me,” he said. “You start with a dark space and subtract sand to reveal light, the opposite of drawing. Each image is fragile—touch it and it vanishes. You create the next frame from the last, like life’s impermanence.”

Working alone in his home office, he’s honed this craft for over 20 years. His previous sand-animated film, The ErlKing, screened at Sundance and Annecy, and he’s written a Jewish-themed musical, The Golem’s Gift, set to premiere in 2026.

“She was stunned,” he said. “She was just a kid with a Jewish symbol.” Despite such incidents, Zelkowicz sees Chevra Kadisha as a beacon of Jewish solidarity. In Columbus, synagogues rotate responsibility for unaffiliated Jews’ funerals, ensuring no one is buried without care. “It’s about taking responsibility for everyone, even those disconnected from the community,” he said.

Reflecting on his work, Zelkowicz acknowledges that fear of death is human. “I can’t say it’s gone, but knowing the community will care for someone I love with gentleness after they’re gone is comforting,” he said.

“They don’t stop being a person deserving of dignity just because they’re no longer breathing.” His film, a tribute to this quiet service, aims to spark conversation about a ritual many overlook, illuminating a profound act of communal love.