Good news from the south: When we arrived at the Sayarim training base on Wednesday morning, the air conditioning was working. That is, outside it was scorching—desert-hell hot—but inside the offices and living quarters, it was cool and pleasant.

It might sound trivial for the AC to work, but in a remote place like Sayarim, deep in the wilderness, it’s no small thing. This massive military base houses thousands of soldiers in the peak of the Israeli summer. Located between the arid Arava and where the Negev blends into the vast Sinai desert just a few miles southwest of here, the climate is punishing.

And what seems like a basic necessity in such extreme conditions simply wasn’t working last week. Yes, right in the middle of a brutal heat wave, with temperatures in Sayarim hitting 46°C (114.8°F), the base’s power system failed. Imagine life here without AC in the barracks and without cold drinking water. You can picture the rest.

It may sound like a minor, routine malfunction—something that could happen anywhere, even in the mighty IDF—but it was much more than that. Not just because of the media waves it created, but because of the deeper impression it left, just as the IDF was preparing for a potential ground operation in Gaza. It gave off the image of an institution struggling to function.

What began as understandable anxiety among young female soldiers quickly escalated—parents at home panicked, and it all exploded into a media frenzy, painting a picture of total breakdown. How could the same IDF that can target a nuclear scientist’s bedroom in Tehran 2,000 kilometers away fail to dispatch an AC technician to refill refrigerant at the largest training base in the Ground Forces?

Anyone who’s sent a child to the army remembers those first few phone calls from basic training. Not every recruit is a tough commando-in-the-making. For some, it’s hard—especially when they’re sent to a far-off desert base in peak summer and the air conditioner fails. “Of course she called me,” said R., the mother of a soldier currently in a course at Sayarim. “Wouldn’t you call home and say you’re passing out from the heat because there’s no AC?”

In parents’ WhatsApp groups, photos of sweat-drenched girls sitting on the floor started circulating. News outlets reported fainting incidents. One mother said her daughter complained, “There’s no cold water in the fountains. Her uniform is soaked in sweat, she’s crying on the phone, ‘Mom, I can’t stop sweating!’”

We had to see it for ourselves. The desert heat around Sayarim is no joke. You can dehydrate easily if you don’t sip water every ten minutes or insist on standing outside in the sun. This vast base is home to the Border Defense Corps training school. It hosts basic and advanced training for combat intelligence soldiers, infantry units along Israel’s borders, female surveillance soldiers and more. All the corps’ command courses—from squad leaders to officers—are held here too. Roughly 3,900 soldiers are spread across several square miles. Most sleep in large two- or three-story dormitories; the rest stay in single-story buildings.

The entire complex is powered by a central energy hub. But without electricity, it’s worthless. “What happened,” said Col. R., the training base commander, “was that the extreme heat melted the electrical cables connected to the switchboards. The temperature inside the panels reached 150°C (302°F), and the cables just melted—that’s what the electricians told me. You have to understand: this place is like a small town. We have huge transformers and massive switchboards, and at the end of the day, power flows through cables. If the cables melt from the heat, nothing helps. There’s no AC and no cold water. This failure shut down 70 percent of the base’s buildings.”

The combat intelligence trainees and those just beginning their basic training in the Border Infantry units were out in the field when the blackout hit, so it didn’t directly affect them. But on base that evening were around 400 female recruits in the surveillance operators’ course, who had enlisted less than a month earlier.

G., the father of one of the trainees, described how quickly the breakdown escalated. “It happened at the end of a very hot day. All they wanted was to get to their air-conditioned rooms, peel off their sweat-soaked uniforms and shower. And suddenly—no AC and no cold water in the drinking stations. Girls started fainting, and others, seeing that, fainted too.

“This is a brand-new cohort—less than a month ago they were civilians, sleeping in their own beds and eating their mother’s food. So is it any wonder they reacted like that? I will say the commanders responded quickly and did their best to reduce the discomfort. But what worries me is—how does a place like this not have backup generators? I mean, seriously—how does the massive IDF not install a backup generator at such a remote base?”

The question is a fair one. In a country where many households keep backup generators in case an Iranian missile knocks out a power station, it’s reasonable to expect a base like Sayarim—where air conditioning is not a luxury but a health necessity—to have backup power.

“This kind of thing hasn’t happened before—not here and not at other bases in the region,” said Col. R. “That’s probably why no one thought to invest in a full-scale generator system for the base. We have a backup generator for the dining hall and a few offices—but that’s it, nothing for the residential areas.

“Usually, we have an electricians’ team that responds immediately to malfunctions, but what happened last week was a full-scale collapse. Once we understood the scope, the army sent in reinforcements—40 personnel worked around the clock to get the system up and running again. And we did more than a quick fix. This base is 40 years old, built by the Americans after the withdrawal from Sinai. The infrastructure is outdated. We could have just patched it up, but we chose to go for a thorough overhaul. We replaced transformers, electric panels, cables—we invested millions of shekels. It took a few days, but now the electricity is fully restored.”

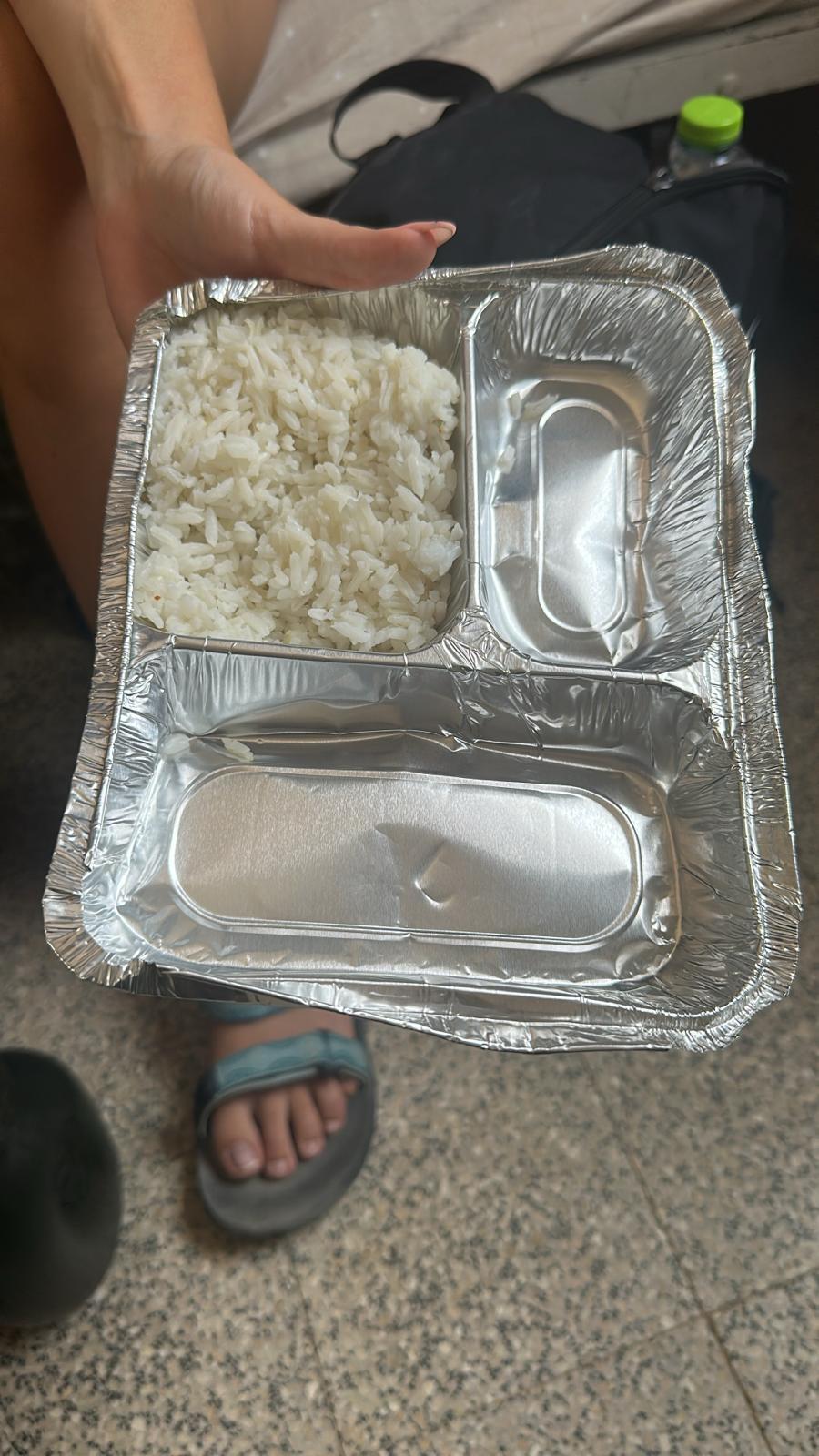

But as R. noted, it did take a few days. Most of the base’s soldiers were sent home, but one platoon of surveillance trainees stayed behind to maintain security. They were moved to a residential area where the AC was still functioning, but they kept in constant contact with their families. Photos began to circulate showing food trays that looked, to put it mildly, unappetizing. Trash piled up near dumpsters. A conscript from central Israel who happened to be at Sayarim that Thursday described the atmosphere as grim.

“The air was stifling. Sitting in a room without AC felt like sitting in an oven. You do nothing and you’re drenched in sweat. Imagine turning on a tap and the water comes out like tea. The only place with air conditioning was the canteen, but how many people can fit in a place the size of a small grocery store?”

R., the mother of another trainee, said the base’s sanitary conditions were terrible, and food shortages were a constant issue. “What’s going on there is a nightmare. The kids are getting diarrhea after eating in the mess hall. My daughter goes back to base with food for 21 days because she’s afraid to eat there—none of her friends eat in the dining hall either. And if they do go in, the food runs out quickly and there’s nothing left.”

These are just a few of the testimonies. Social media is full of others. Exaggeration has become part of the story. According to R., no soldiers actually fainted. The base doctor examined all who complained and diagnosed them with exhaustion. They were moved to air-conditioned rooms and told to rest. Two soldiers were evacuated to Soroka, but for unrelated medical issues.

Electricity gradually returned to the base. By Tuesday, air conditioning was working in all residential areas. Lt. Col. Shai, head of the surveillance operator training department, said the power failure triggered a natural crisis many new recruits experience. “Every soldier needs time to adjust—to the army, to the desert climate, to the rules, to this new way of life. Sharing a room with other girls, no privacy in the showers, only one hour a day to use your phone—and when you call home, they ask how much you slept, what you ate, how the conditions are, how your commanders treat you. Then suddenly you’re on kitchen duty, scrubbing giant pots and serving food in a massive mess hall feeding thousands—and you’ve been in the army for only two weeks. Then, right in the middle of the heat wave, there’s no electricity or AC. It’s the kind of thing that throws everything out of proportion.”

We had talked about the base’s energy and power systems. Col. R. gave us a rundown of the millions the army is now investing in new infrastructure—but above all, it seemed the thing he took most personally was the dining hall. If there’s one thing he takes pride in, it’s the food.

We told him we’d eaten on the way—spinach-and-cheese pastry and a sesame bagel we picked up in Jaffa—but that didn’t deter him. R. insisted we follow him to the mess hall.

There, he introduced us to the kitchen manager, Ofir. “I brought him here from the West Bank Division,” R. said proudly, patting him on the back. “He’s a real gem—I’m very, very proud of him. He’s only been here two months, but you can already feel the difference.”

The duty soldiers were bringing out large tubs of hummus and red and white cabbage salads. Before that, they had served trays of vegetable salads and matbucha. At the gluten-free and vegan station, there were bowls of lettuce, lentils, quinoa and vegetable patties. One large tray held tofu cubes with cooked vegetables. At the meat station, there were trays of schnitzels, shredded beef, rice with vegetables and oven-roasted potatoes.

“I invite that mother you spoke to—let her come eat here,” R. said. “There’s a stigma about our food, and it’s just not true. I get calls from moms saying, ‘My daughter is hungry,’ and I tell them, ‘Send her to my kitchen.’ There’s no shortage of food here. We’ve got enough to feed a whole army. And another thing—there’s no food poisoning here. No stomach bugs. This place is checked for sanitation three times a day.”

They set up a table for us, loaded with everything mentioned above. No excuses were accepted—we had to eat, with Col. R. and the kitchen manager watching to make sure we didn’t just taste but actually swallowed. Tal, the photographer, tried the shredded beef. I went for the schnitzel. It’s been two days since, and nothing happened. We made it out alive.