Paul AdamsDiplomatic Correspondent

Paul AdamsDiplomatic Correspondent  BBC

BBCEarlier this month, a Palestinian diplomat called Husam Zomlot was invited to a discussion at the Chatham House think tank in London.

Belgium had just joined the UK, France and other countries in promising to recognise a Palestinian state at the United Nations in New York. And Dr Zomlot was clear that this was a significant moment.

“What you will see in New York might be the actual last attempt at implementing the two-state solution,” he warned.

“Let that not fail.”

Weeks on, that has now come to pass. The UK, Canada and Australia, who are all traditionally strong allies of Israel, have finally taken this step.

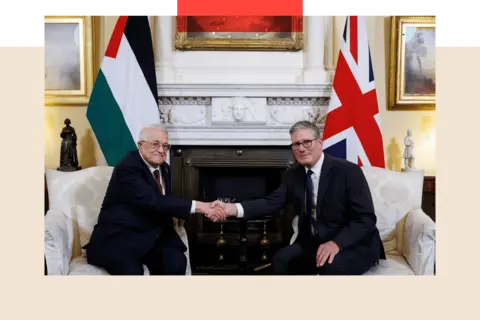

Sir Keir Starmer announced the UK’s move in a video posted on social media.

In it he said: “In the face of the growing horror in the Middle East, we are acting to keep alive the possibility of peace and of a two-state solution.

“That means a safe and secure Israel alongside a viable Palestinian state – at the moment we have neither.”

More than 150 countries had previously recognised a Palestinian state but the addition of the UK and the other countries is seen by many as a significant moment.

“Palestine has never been more powerful worldwide than it is now,” says Xavier Abu Eid, a former Palestinian official.

“The world is mobilised for Palestine.”

But there are complicated questions to answer, including what is Palestine and is there even a state to recognise?

Shutterstock

ShutterstockFour criteria for statehood are listed in the 1933 Montevideo Convention. Palestine can justifiably lay claim to two: a permanent population (although the war in Gaza has put this at enormous risk) and the capacity to enter into international relations – Dr Zomlot is proof of the latter.

But it doesn’t yet fit the requirement of a “defined territory”.

With no agreement on final borders (and no actual peace process), it’s difficult to know with any certainty what is meant by Palestine.

For the Palestinians themselves, their longed-for state consists of three parts: East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. All were conquered by Israel during the 1967 Six Day War.

Even a cursory glance at a map shows where the problems begin.

The West Bank and Gaza Strip have been geographically separated by Israel for three quarters of a century, since Israel’s independence in 1948.

In the West Bank, the presence of the Israeli military and Jewish settlers means the Palestinian Authority, established after the Oslo Accords peace deals of the 1990s, administers only around 40% of the territory. Since 1967, the expansion of settlements has eaten away at the West Bank, breaking it up into an increasingly fragmented political and economic entity.

Meanwhile, East Jerusalem, which Palestinians regard as their capital, has been ringed with Jewish settlements, gradually cutting off the city from the West Bank.

Gaza’s fate, of course, has been much worse. After almost two years of war, triggered by the Hamas attacks of October 2023, much of the territory has been obliterated.

But as if all this wasn’t enough to fix, there’s a fourth criteria laid down in the Montevideo convention that is needed to recognise statehood: a functioning government.

And this marks a great challenge for Palestinians.

‘We need a new leadership’

Back in 1994, an agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) led to the creation of the Palestinian National Authority (known simply as the Palestinian Authority or PA), which exercised partial civil control over Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank.

But since a bloody conflict in 2007 between Hamas and the main PLO faction Fatah, Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank have been ruled by two rival governments: Hamas in Gaza and the internationally recognised Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, whose president is Mahmoud Abbas.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesThat’s 77 years of geographical separation and 18 years of political division: a long time for the West Bank and Gaza Strip to drift apart.

Palestinian politics has ossified in the meantime, leaving most Palestinians cynical about their leadership and pessimistic about the chances of any kind of internal reconciliation, let alone progress towards statehood.

The last presidential and parliamentary elections were in 2006, which means that no Palestinian under the age of 36 has ever voted in the West Bank or Gaza.

“That we haven’t had elections in all of this time just boggles the mind,” says Palestinian lawyer Diana Buttu.

“We need a new leadership.”

MAHMUD HAMS/AFP via Getty Images

MAHMUD HAMS/AFP via Getty ImagesIn the wake of the war which erupted in Gaza in October 2023, the issue has become even more acute.

Faced with the deaths of tens of thousands of its citizens, Abbas’s Palestinian Authority, watching from its headquarters in the West Bank, has been largely reduced to the role of helpless bystander.

Years of internal discord

Tensions within the ranks of leadership date back years.

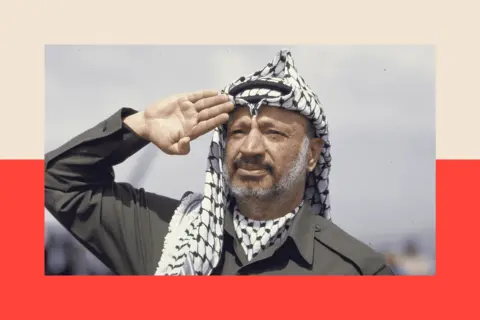

When the PLO chairman, Yasser Arafat, returned from years in exile to lead the Palestinian Authority, local Palestinian politicians found themselves mostly side-lined.

“Insiders” came to resent the domineering style of Arafat’s “outsiders”. Rumours of corruption in Arafat’s circle did little to enhance the PA’s reputation.

More importantly, the newly formed Palestinian Authority seemed incapable of halting Israel’s gradual colonisation of the West Bank or delivering on the promise of independence and sovereignty raised so tantalisingly by Arafat’s historic handshake with the former Israeli prime minister, Yizhak Rabin, on the White House lawn in September 1993.

REUTERS/Gary Hershorn

REUTERS/Gary HershornThe subsequent years were not conducive to a smooth political evolution, dominated as they were by failed peace initiatives, the continued expansion of Jewish settlements, violence by extremists on both sides, Israel’s political slide to the right and that violent schism in 2007 between Hamas and Fatah.

“In the normal course of events, new figures, new generations would have emerged,” says the Palestinian historian Yezid Sayigh.

“But that has been impossible…Palestinians in the occupied territories are fragmented enormously into separate little spaces, and that has made it almost impossible for new figures to emerge and coalesce.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne figure did emerge, however: Marwan Barghouti.

Born and raised in the West Bank, at the age of 15 he became active in Fatah, the PLO faction led by Arafat.

Barghouti emerged as a popular leader during the second Palestinian uprising, before being arrested and charged with planning deadly attacks in which five Israelis were killed.

He has always denied the charges but has been in an Israeli prison since 2002.

And yet when Palestinians talk about possible future leaders, they end up talking about a man who has been locked up for almost a quarter of a century.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesA recent opinion poll by the West Bank based Palestinian Centre for Policy and Survey Research found that 50% of Palestinians would choose Barghouti as president, well ahead of Abbas, who has held the position since 2005.

Despite being a senior member of Fatah, which has long been in conflict with Hamas, his name is thought to feature prominently on the list of political prisoners Hamas wants freed in return for Israeli hostages held in Gaza.

But Israel has not given any indication of a willingness to release him.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesIn mid-August, a video emerged, showing a gaunt, frail 66-year old Barghouti being taunted by Israel’s security minister, Itamar Ben Gvir.

It was the first time Barghouti had been seen publicly for years.

Netanyahu and Palestinian statehood

Even before the Gaza war, Benjamin Netanyahu’s opposition to Palestinian statehood was unambiguous.

In February 2024, he said that, “Everyone knows that I am the one who for decades blocked the establishment of a Palestinian state that would endanger our existence.”

Despite international calls for the Palestinian Authority to resume control over Gaza, Netanyahu insists that there will be no role for the PA in Gaza’s future governance, arguing that Abbas has not condemned the Hamas attacks of 7 October.

In August, Israel gave final approval for a settlement project that would effectively cut East Jerusalem off from the West Bank. Plans for 3,400 homes were approved, with Israel’s finance minister Bezalel Smotrich saying the plan would bury the idea of a Palestinian state “because there is nothing to recognise and no one to recognise”.

This, argues Mr Sayigh, is hardly a new state of affairs.

“You could get the Archangel Michael down to earth and have him head the Palestinian Authority, but it wouldn’t make any difference. Because you have to work under conditions that make any kind of success totally impossible.

“And that has been the case for a long time.”

Reuters

ReutersOne thing is certain: if a Palestinian state does emerge, Hamas will not be running it.

A declaration drawn up in July at the end of a three day conference sponsored by France and Saudi Arabia declared that “Hamas must end its rule in Gaza and hand over its weapons to the Palestinian authority.”

The “New York declaration” was endorsed by all Arab states and subsequently adopted by 142 members of the UN General Assembly.

For its part, Hamas says it’s ready to hand over authority in Gaza to an independent administration of technocrats.

Is symbolism of recognition enough?

With Barghouti in jail, Abbas approaching 90 years of age, Hamas decimated and the West Bank in pieces, it’s clear that Palestine lacks leadership and coherence. But that doesn’t mean international recognition is meaningless.

“It could actually be very valuable,” says Diana Buttu, though she cautions: “It depends why these countries are doing it and what their intent is.”

A British government official, speaking on condition of anonymity, told me that the mere symbolism of recognition was not enough.

“The question is whether we can get progress towards something so that UNGA [United Nations General Assembly] doesn’t just become a recognition party.”

Shutterstock

ShutterstockThe New York Declaration committed signatories including Britain to taking “tangible, timebound and irreversible steps for the peaceful settlement of the question of Palestine.”

Officials in London point to the declaration’s references to the unification of Gaza and the West Bank, support for the PA and Palestinian elections (as well as an Arab reconstruction plan for Gaza) as the sorts of steps that need to follow recognition.

But they know the obstacles are formidable.

Israel remains implacably opposed and has threatened to retaliate through formal annexation of parts or all of the West Bank.

Meanwhile, the US president Donald Trump has made clear his displeasure about the subject, saying on Thursday: “I have a disagreement with the prime minister on that score.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn August, the US also took the unusual step of revoking or denying visas for dozens of Palestinian officials, in a possible violation of the UN’s own rules.

The US holds a veto at the UN on any recognition of a Palestinian state and Trump still appears wedded to a version of his so-called “Riviera Plan” in which the US would take “a long-term ownership position” over Gaza.

Crucially, the plan says nothing about the Palestinian Authority, referring only to “reformed Palestinian self-governance”, or any future connection between Gaza and the West Bank.

The long-term future for Gaza may lie somewhere, between the New York Declaration, Trump’s plan and the Arab reconstruction plan.

All the plans, in their own very different ways, hope to salvage something out of the calamity that has befallen Gaza over the past two years. And whatever does emerge, it will need to answer the question of what Palestine and its leadership looks like.

But for Palestinians like Diana Buttu, there’s a much more pressing matter. What she would really prefer, she says, is for these countries to prevent more killing.

“And do something to stop it, rather than focus on the issue of statehood.”

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.